Linked List

What’s a Linked List?

-

Regardless of which language we start coding in, one of the first things that we encounter are data structures, which are the different ways that we can organize our data; variables, arrays, hashes, and objects are all types of data structures. But these are still just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to data structures; there are a lot more, some of which start to sound super complicated the more that you hear about them.

-

One of those complicated things for me has always been linked lists. I’ve known about linked lists for a few years now, but I can never quite keep them straight in my head. I only really think about them when I’m preparing for (or sometimes, in the middle of) a technical interview, and someone asks me about them. I’ll do a little research and think that I understand what they’re about, but after a few weeks, I forget them again. The whole thing is pretty inefficient, and it all stems from the fact that I know they exist, but I don’t fundamentally understand them! So, it’s time to change that and answer the question: what on earth is a linked list, anyway?

Linear data structures

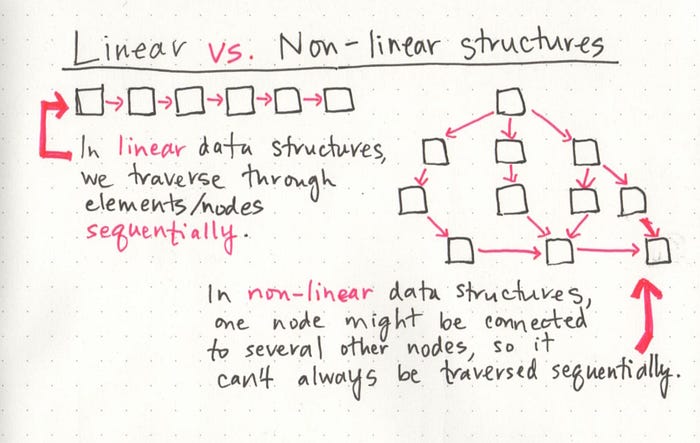

If we really want to understand the basics of linked lists, it’s important that we talk about what type of data structure they are. One characteristic of linked lists is that they are linear data structures, which means that there is a sequence and an order to how they are constructed and traversed. We can think of a linear data structure like a game of hopscotch: in order to get to the end of the list, we have to go through all of the items in the list in order, or sequentially. Linear structures, however, are the opposite of non-linear structures. In non-linear data structures, items don’t have to be arranged in order, which means that we could traverse the data structure non-sequentially.

We might not always realize it, but we all work with linear and non-linear data structures everyday! When we organize our data into hashes (sometimes called dictionaries), we’re implementing a non-linear data structure. Trees and graphs are also non-linear data structures that we traverse in different ways, but we’ll talk more about them in more depth later in the year.

Similarly, when we use arrays in our code, we’re implementing a linear data structure! It can be helpful to think of arrays and linked lists as being similar in the way that we sequence data. In both of these structures, order matters. But what makes arrays and linked lists different?

Memory management

- The biggest differentiator between arrays and linked lists is the way that they use memory in our machines. Those of us who work with dynamically typed languages like Ruby, JavaScript, or Python don’t have to think about how much memory an array uses when we write our code on a day to day basis because there are several layers of abstraction that end up with us not having to worry about memory allocation at all.

But that doesn’t mean that memory allocation isn’t happening! Abstraction isn’t magic, it’s just the simplicity of hiding away things that you don’t need to see or deal with all of the time. Even if we don’t have to think about memory allocation when we write code, if we want to truly understand what’s going on in a linked list and what makes it powerful, we have to get down to the rudimentary level.

- We’ve already learned about binary and how data can be broken up into bits and bytes. Just as characters, numbers, words, sentences require bytes of memory to represent them, so do data structures.

When an array is created, it needs a certain amount of memory. If we had 7 letters that we needed to store in an array, we would need 7 bytes of memory to represent that array. But, we’d need all of that memory in one contiguous block. That is to say, our computer would need to locate 7 bytes of memory that was free, one byte next to the another, all together, in one place.

- On the other hand, when a linked list is born, it doesn’t need 7 bytes of memory all in one place. One byte could live somewhere, while the next byte could be stored in another place in memory altogether! Linked lists don’t need to take up a single block of memory; instead, the memory that they use can be scattered throughout.

- The fundamental difference between arrays and linked lists is that arrays are static data structures, while linked lists are dynamic data structures. A static data structure needs all of its resources to be allocated when the structure is created; this means that even if the structure was to grow or shrink in size and elements were to be added or removed, it still always needs a given size and amount of memory. If more elements needed to be added to a static data structure and it didn’t have enough memory, you’d need to copy the data of that array, for example, and recreate it with more memory, so that you could add elements to it.

* On the other hand, a dynamic data structure can shrink and grow in memory. It doesn’t need a set amount of memory to be allocated in order to exist, and its size and shape can change, and the amount of memory it needs can change as well.

By now, we can already begin to see some major differences between arrays and linked lists. But this begs the question: what allows a linked list to have its memory scattered everywhere? To answer this question, we need to look at the way that a linked list is structured.

Parts of a linked list

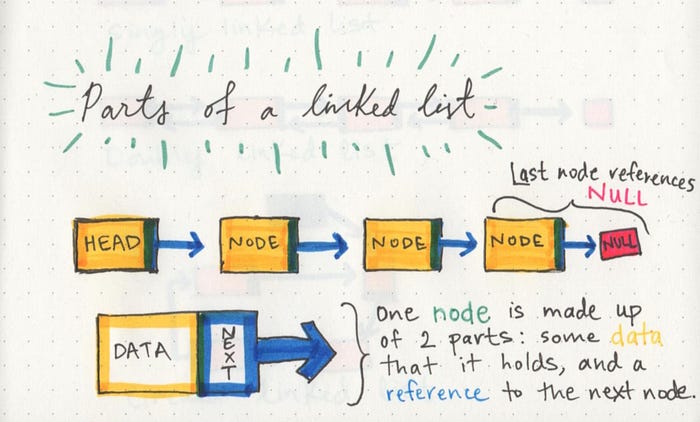

- A linked list can be small or huge, but no matter the size, the parts that make it up are actually fairly simple. A linked list is made up of a series of nodes, which are the elements of the list.

The starting point of the list is a reference to the first node, which is referred to as the head. Nearly all linked lists must have a head, because this is effectively the only entry point to the list and all of its elements, and without it, you wouldn’t know where to start! The end of the list isn’t a node, but rather a node that points to null, or an empty value.

Lists for all shapes and sizes

-

Even though the parts of a linked list don’t change, the way that we structure our linked lists can be quite different. Like most things in software, depending on the problem that we’re trying to solve, one type of linked lists might be a better tool for the job than another.

-

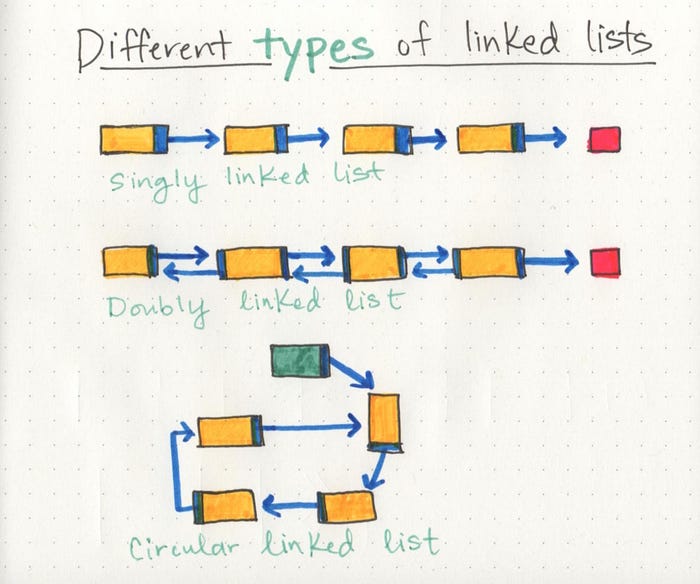

Singly linked lists are the simplest type of linked list, based solely on the fact that they only go in one direction. There is a single track that we can traverse the list in; we start at the head node, and traverse from the root until the last node, which will end at an empty null value.

-

But just as a node can reference its subsequent neighbor node, it can also have a reference pointer to its preceding node, too! This is what we call a doubly linked list, because there are two references contained within each node: a reference to the next node, as well as the previous node. This can be helpful if we wanted to be able to traverse our data structure not just in a single track or direction, but also backwards, too.

For example, if we wanted to be able to hop between one node and the node previous without having to go back to the very beginning of the list, a doubly linked list would be a better data structure than a singly linked list. However, everything requires space and memory, so if our node had to store two reference pointers instead of just one, that would be another thing to consider.

Hey, so, what even is Big O?

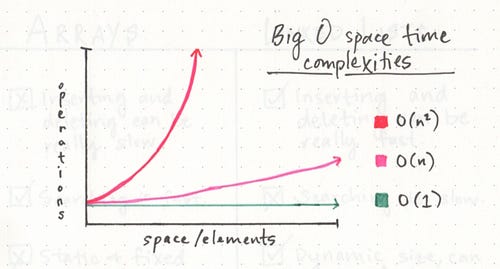

One way to think about Big O notation is a way to express the amount of time that a function, action, or algorithm takes to run based on how many elements we pass to that function.

For example, if we have a list of the number 1–10, and we wanted to write an algorithm that multiplied each number by 10, we’d think about how much time that algorithm would take to multiply ten numbers. But what if instead of ten numbers, we had ten thousand? Or a million? Or tens of millions? That’s exactly what Big O Notation takes into account: the speed and efficiency with which something functions when its input grows to be any (crazy big!) size.

I really love the way that Parker Phinney describes what Big O notation is used for in his awesome Interview Cake blog post. The way that he explains it, Big O Notation is all about the way an algorithm grows when it runs: Some external factors affect the time it takes for a function to run: the speed of the processor, what else the computer is running, etc.

So it’s hard to make strong statements about the exact runtime of an algorithm. Instead we use big O notation to express how quickly its runtime grows.

If you do a little bit of research on Big O Notation, you’ll quickly find that there are a ton of different equations used to define the space and time complexity of an algorithm, and most of them involve an O (referred to as just “O” or sometimes as “order”), and a variable n, where n is the size of the input (think back to our our ten, thousands, or millions of numbers).

As far as linked lists go, however, the two types of Big O equations to remember are O(1) and O(n).

- An O(1) function takes constant time, which is to say that it doesn’t matter how many elements we have, or how huge our input is: it’ll always take the same amount of time and memory to run our algorithm. An O(n) function is linear, which means that as our input grows (from ten numbers, to ten thousand, to ten million), the space and time that we need to run that algorithm grows linearly. For a little contrast, we can also compare these two functions to something starkly different: an O(n²) function, which clearly takes exponentially more time and memory the more elements that you have. It’s pretty safe to say that we want to avoid O(n²) algorithms, just from looking at that crazy red line!

Growing a linked list

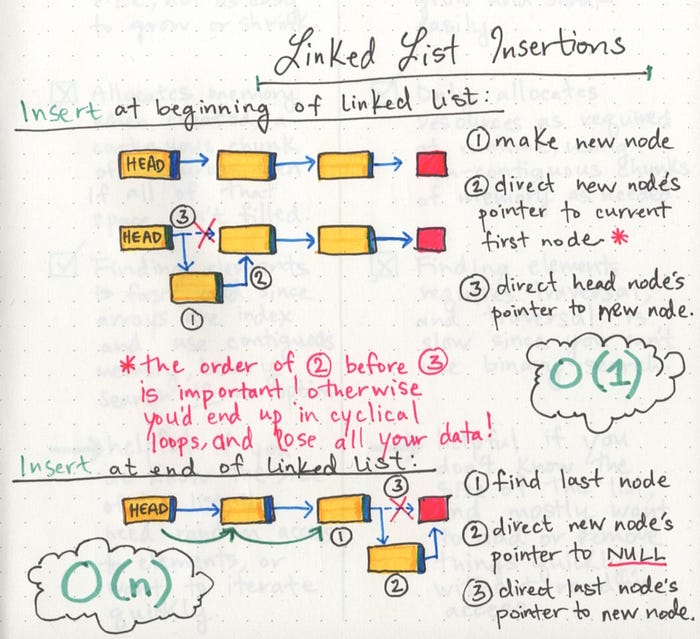

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll work with a singly linked list in these examples. We’ll start with the simplest place we can insert an element into a linked list: at the very beginning. This is fairly easy to do, since we don’t need to go through our entire list; instead we just start at the beginning.

-

First, we find the head node of the linked list.

-

Next, we’ll make our new node, and set its pointer to the current first node of the list.

-

Lastly, we rearrange our head node’s pointer to point at our new node.

-

Still, that process isn’t too hard to implement (and hopefully shouldn’t be too difficult to code) once you can remember those three steps.

-

Inserting an element at the beginning of a linked list is particularly nice and efficient because it takes the same amount of time, no matter how long our list is, which is to say it has a space time complexity that is constant, or O(1).

- But inserting an element at the end of a linked list is a different story. The interesting thing here is that the steps you take to actually do the inserting are the exact same:

-

Find the node we want to change the pointer of (in this case, the last node)

-

Create the new node we want to insert and set its pointer (in this case, to null)

-

Direct the preceding node’s pointer to our new node

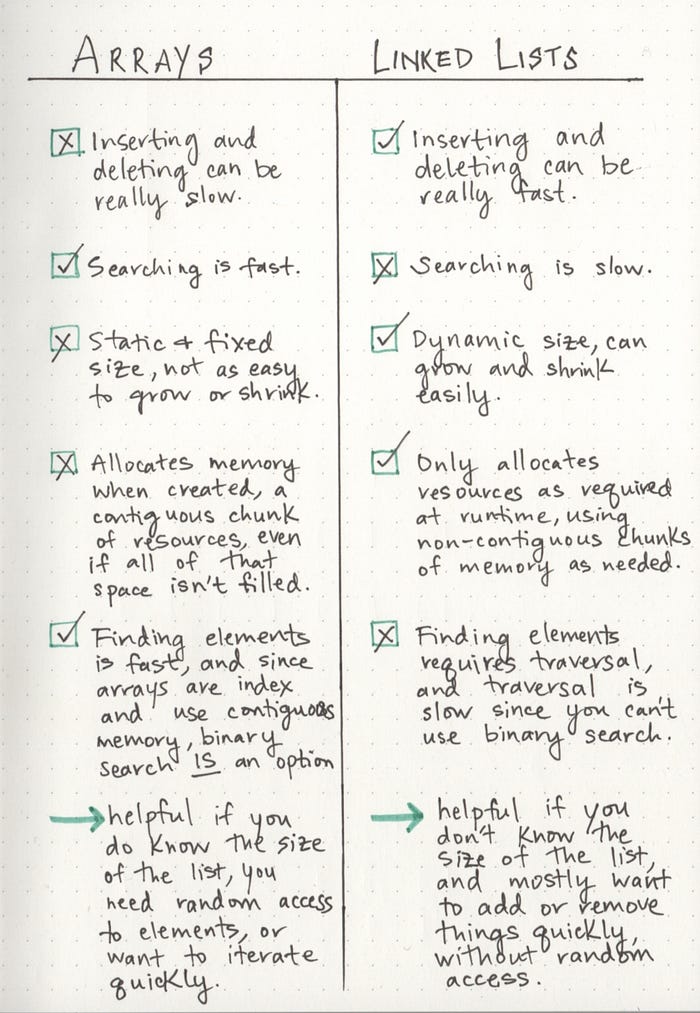

To list or not to list?

A good rule of thumb for remember the characteristics of linked lists is this:

a linked list is usually efficient when it comes to adding and removing most elements, but can be very slow to search and find a single element.

- If you ever find yourself having to do something that requires a lot of traversal, iteration, or quick index-level access, a linked list could be your worst enemy. In those situations, an array might be a better solution, since you can find things quickly (a single chunk of allocated memory), and you can use an index to quickly retrieve a random element in the middle or end of the list without having to take the time to traverse through the whole entire thing.

However, if you find yourself wanting to add a bunch of elements to a list and aren’t worried about finding elements again later, or if you know that you won’t need to traverse through the entirety of the list, a linked list could be your new best friend.