Django CRUD and Forms

-

An HTML Form is a group of one or more fields/widgets on a web page, which can be used to collect information from users for submission to a server. Forms are a flexible mechanism for collecting user input because there are suitable widgets for entering many different types of data, including text boxes, checkboxes, radio buttons, date pickers and so on. Forms are also a relatively secure way of sharing data with the server, as they allow us to send data in POST requests with cross-site request forgery protection.

-

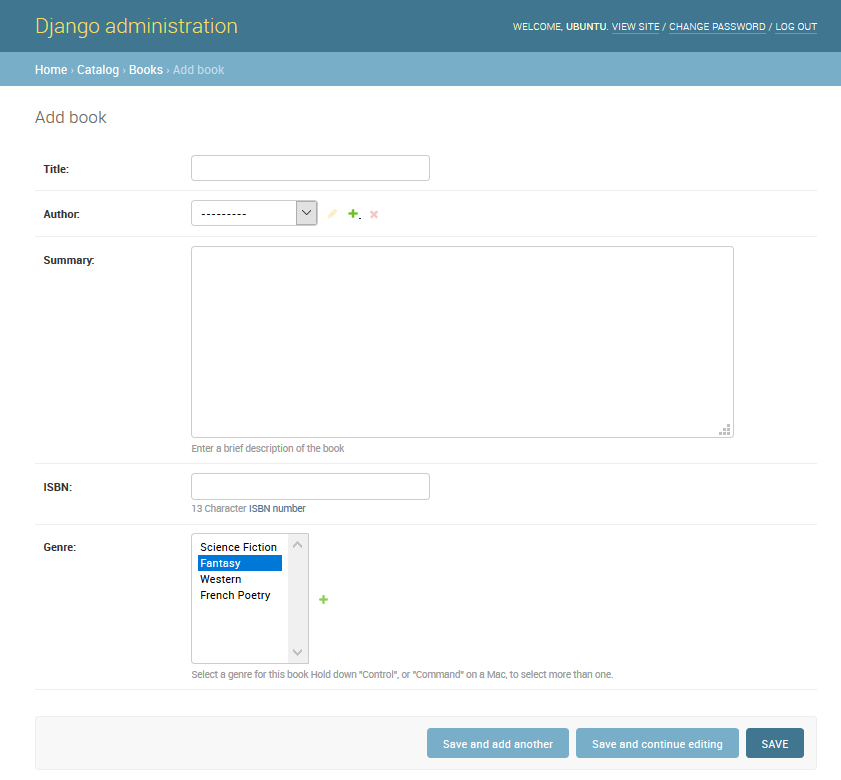

While we haven’t created any forms in this tutorial so far, we’ve already encountered them in the Django Admin site — for example, the screenshot below shows a form for editing one of our Book models, comprised of a number of selection lists and text editors.

- Working with forms can be complicated! Developers need to write HTML for the form, validate and properly sanitize entered data on the server (and possibly also in the browser), repost the form with error messages to inform users of any invalid fields, handle the data when it has successfully been submitted, and finally respond to the user in some way to indicate success. Django Forms take a lot of the work out of all these steps, by providing a framework that lets you define forms and their fields programmatically, and then use these objects to both generate the form HTML code and handle much of the validation and user interaction.

In this tutorial, we’re going to show you a few of the ways you can create and work with forms, and in particular, how the generic editing views can significantly reduce the amount of work you need to do to create forms to manipulate your models. Along the way, we’ll extend our LocalLibrary application by adding a form to allow librarians to renew library books, and we’ll create pages to create, edit and delete books and authors (reproducing a basic version of the form shown above for editing books).

HTML Forms

- The form is defined in HTML as a collection of elements inside

<form>...</form>tags, containing at least one input element of type=”submit”.

<form action="/team_name_url/" method="post">

<label for="team_name">Enter name: </label>

<input id="team_name" type="text" name="name_field" value="Default name for team.">

<input type="submit" value="OK">

</form>

-

While here we just have one text field for entering the team name, a form may have any number of other input elements and their associated labels. The field’s type attribute defines what sort of widget will be displayed. The name and id of the field are used to identify the field in JavaScript/CSS/HTML, while value defines the initial value for the field when it is first displayed. The matching team label is specified using the label tag (see “Enter name” above), with a for field containing the id value of the associated input.

-

The submit input will be displayed as a button (by default) that can be pressed by the user to upload the data in all the other input elements in the form to the server (in this case, just the team_name). The form attributes define the HTTP method used to send the data and the destination of the data on the server (action):

-

action: The resource/URL where data is to be sent for processing when the form is submitted. If this is not set (or set to an empty string), then the form will be submitted back to the current page URL.

-

method: The HTTP method used to send the data: post or get.

The POST method should always be used if the data is going to result in a change to the server’s database because this can be made more resistant to cross-site forgery request attacks.

The GET method should only be used for forms that don’t change user data (e.g. a search form). It is recommended for when you want to be able to bookmark or share the URL.

- The role of the server is first to render the initial form state — either containing blank fields or pre-populated with initial values. After the user presses the submit button, the server will receive the form data with values from the web browser and must validate the information. If the form contains invalid data, the server should display the form again, this time with user-entered data in “valid” fields and messages to describe the problem for the invalid fields. Once the server gets a request with all valid form data, it can perform an appropriate action (e.g. saving the data, returning the result of a search, uploading a file, etc.) and then notify the user.

As you can imagine, creating the HTML, validating the returned data, re-displaying the entered data with error reports if needed, and performing the desired operation on valid data can all take quite a lot of effort to “get right”. Django makes this a lot easier, by taking away some of the heavy lifting and repetitive code!

Django form handling process

- Django’s form handling uses all of the same techniques that we learned about in previous tutorials (for displaying information about our models): the view gets a request, performs any actions required including reading data from the models, then generates and returns an HTML page (from a template, into which we pass a context containing the data to be displayed). What makes things more complicated is that the server also needs to be able to process data provided by the user, and redisplay the page if there are any errors.

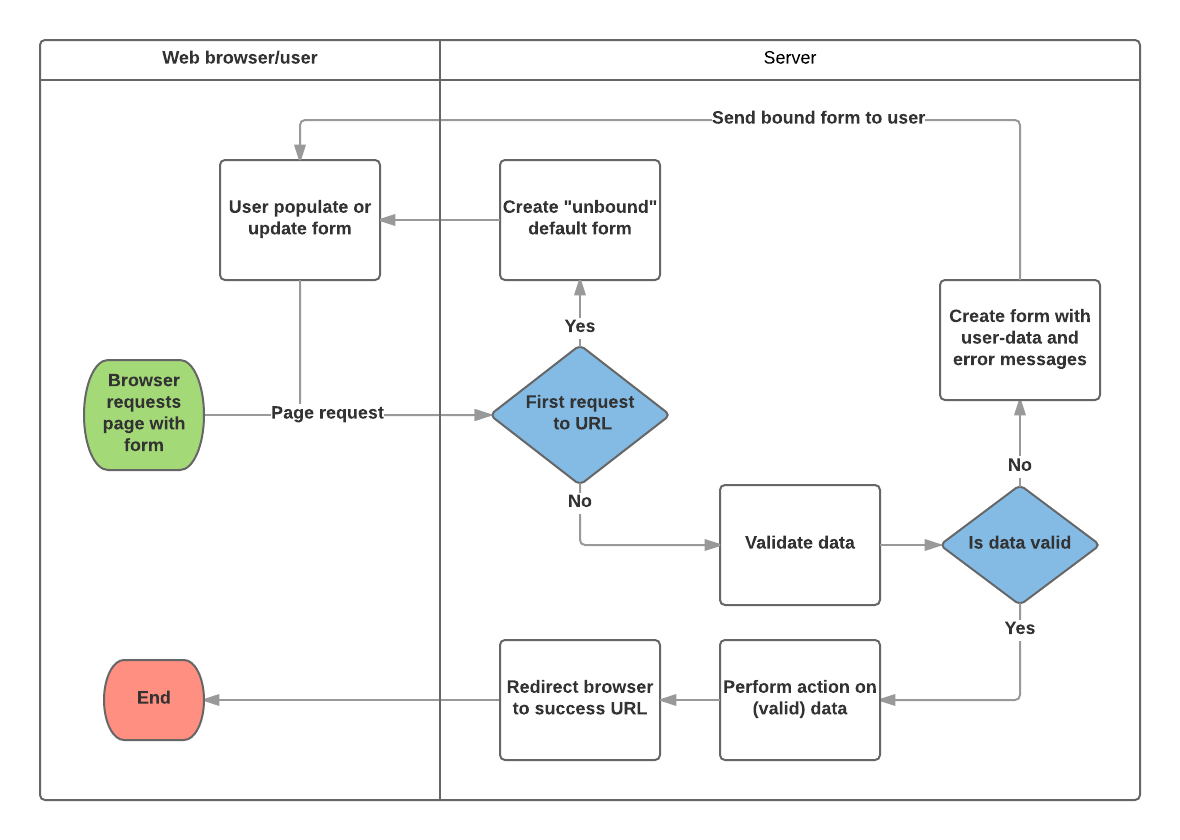

A process flowchart of how Django handles form requests is shown below, starting with a request for a page containing a form (shown in green).

Based on the diagram above, the main things that Django’s form handling does are:

Display the default form the first time it is requested by the user.

The form may contain blank fields (e.g. if you’re creating a new record), or it may be pre-populated with initial values (e.g. if you are changing a record, or have useful default initial values).

The form is referred to as unbound at this point, because it isn’t associated with any user-entered data (though it may have initial values).

Receive data from a submit request and bind it to the form. Binding data to the form means that the user-entered data and any errors are available when we need to redisplay the form.

Clean and validate the data.

Cleaning the data performs sanitization of the input (e.g. removing invalid characters that might be used to send malicious content to the server) and converts them into consistent Python types.

Validation checks that the values are appropriate for the field (e.g. are in the right date range, aren’t too short or too long, etc.)

If any data is invalid, re-display the form, this time with any user populated values and error messages for the problem fields.

If all data is valid, perform required actions (e.g. save the data, send an email, return the result of a search, upload a file, etc.)

Once all actions are complete, redirect the user to another page.

Renew-book form using a Form and function view

- Next, we’re going to add a page to allow librarians to renew borrowed books. To do this we’ll create a form that allows users to enter a date value. We’ll seed the field with an initial value 3 weeks from the current date (the normal borrowing period), and add some validation to ensure that the librarian can’t enter a date in the past or a date too far in the future. When a valid date has been entered, we’ll write it to the current record’s BookInstance.due_back field.

The example will use a function-based view and a Form class. The following sections explain how forms work, and the changes you need to make to our ongoing LocalLibrary project.

Form

- The Form class is the heart of Django’s form handling system. It specifies the fields in the form, their layout, display widgets, labels, initial values, valid values, and (once validated) the error messages associated with invalid fields. The class also provides methods for rendering itself in templates using predefined formats (tables, lists, etc.) or for getting the value of any element (enabling fine-grained manual rendering).

Declaring a Form

- The declaration syntax for a Form is very similar to that for declaring a Model, and shares the same field types (and some similar parameters). This makes sense because in both cases we need to ensure that each field handles the right types of data, is constrained to valid data, and has a description for display/documentation.

from django import forms

class RenewBookForm(forms.Form):

renewal_date = forms.DateField(help_text="Enter a date between now and 4 weeks (default 3).")

Validation

- Django provides numerous places where you can validate your data. The easiest way to validate a single field is to override the method

clean_<fieldname>()for the field you want to check. So for example, we can validate that entered renewal_date values are between now and 4 weeks by implementing clean_renewal_date() as shown below.

Update your forms.py file so it looks like this:

import datetime

from django import forms

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError

from django.utils.translation import ugettext_lazy as _

class RenewBookForm(forms.Form):

renewal_date = forms.DateField(help_text="Enter a date between now and 4 weeks (default 3).")

def clean_renewal_date(self):

data = self.cleaned_data['renewal_date']

# Check if a date is not in the past.

if data < datetime.date.today():

raise ValidationError(_('Invalid date - renewal in past'))

# Check if a date is in the allowed range (+4 weeks from today).

if data > datetime.date.today() + datetime.timedelta(weeks=4):

raise ValidationError(_('Invalid date - renewal more than 4 weeks ahead'))

# Remember to always return the cleaned data.

return data

- There are two important things to note. The first is that we get our data using self.cleaned_data[‘renewal_date’] and that we return this data whether or not we change it at the end of the function. This step gets us the data “cleaned” and sanitized of potentially unsafe input using the default validators, and converted into the correct standard type for the data (in this case a Python datetime.datetime object).

The second point is that if a value falls outside our range we raise a ValidationError, specifying the error text that we want to display in the form if an invalid value is entered. The example above also wraps this text in one of Django’s translation functions ugettext_lazy() (imported as _()), which is good practice if you want to translate your site later.

URL configuration

- Before we create our view, let’s add a URL configuration for the renew-books page. Copy the following configuration to the bottom of locallibrary/catalog/urls.py.

urlpatterns += [

path('book/<uuid:pk>/renew/', views.renew_book_librarian, name='renew-book-librarian'),

]

The URL configuration will redirect URLs with the format /catalog/book/<bookinstance_id>/renew/ to the function named renew_book_librarian() in views.py, and send the BookInstance id as the parameter named pk. The pattern only matches if pk is a correctly formatted uuid.

View

-

As discussed in the Django form handling process above, the view has to render the default form when it is first called and then either re-render it with error messages if the data is invalid, or process the data and redirect to a new page if the data is valid. In order to perform these different actions, the view has to be able to know whether it is being called for the first time to render the default form, or a subsequent time to validate data.

-

For forms that use a POST request to submit information to the server, the most common pattern is for the view to test against the POST request type (if request.method == ‘POST’:) to identify form validation requests and GET (using an else condition) to identify the initial form creation request. If you want to submit your data using a GET request, then a typical approach for identifying whether this is the first or subsequent view invocation is to read the form data (e.g. to read a hidden value in the form).

The book renewal process will be writing to our database, so, by convention, we use the POST request approach. The code fragment below shows the (very standard) pattern for this sort of function view.

import datetime

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from django.http import HttpResponseRedirect

from django.urls import reverse

from catalog.forms import RenewBookForm

def renew_book_librarian(request, pk):

book_instance = get_object_or_404(BookInstance, pk=pk)

# If this is a POST request then process the Form data

if request.method == 'POST':

# Create a form instance and populate it with data from the request (binding):

form = RenewBookForm(request.POST)

# Check if the form is valid:

if form.is_valid():

# process the data in form.cleaned_data as required (here we just write it to the model due_back field)

book_instance.due_back = form.cleaned_data['renewal_date']

book_instance.save()

# redirect to a new URL:

return HttpResponseRedirect(reverse('all-borrowed') )

# If this is a GET (or any other method) create the default form.

else:

proposed_renewal_date = datetime.date.today() + datetime.timedelta(weeks=3)

form = RenewBookForm(initial={'renewal_date': proposed_renewal_date})

context = {

'form': form,

'book_instance': book_instance,

}

return render(request, 'catalog/book_renew_librarian.html', context)