Wireframe

What Exactly Is Wireframing?

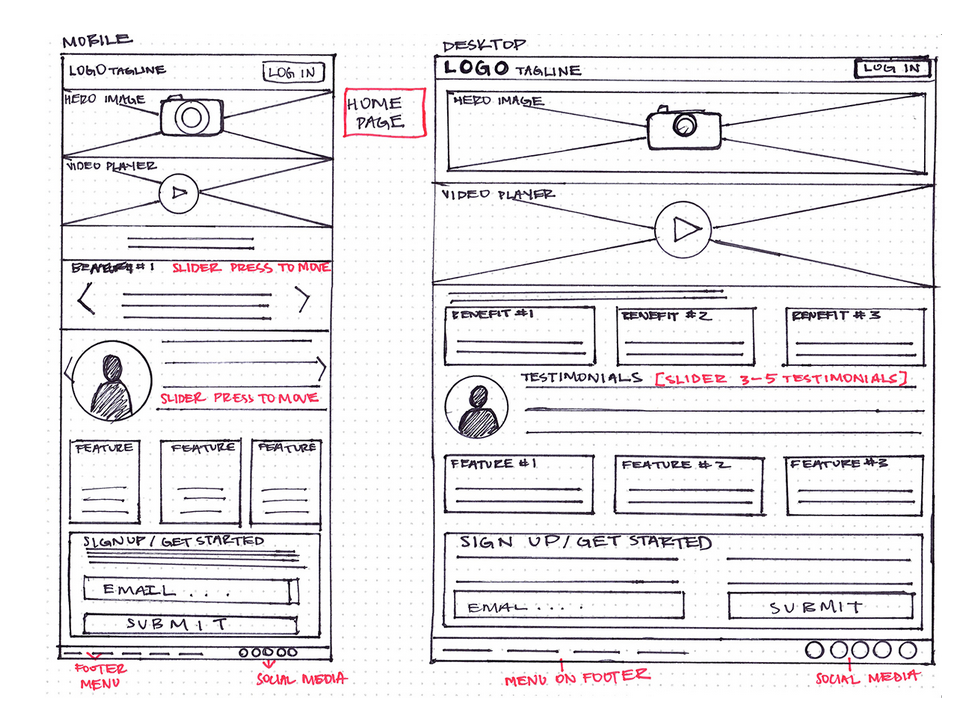

Not dissimilar to an architectural blueprint, a wireframe is a two-dimensional skeletal outline of a webpage or app. Wireframes provide a clear overview of the page structure, layout, information architecture, user flow, functionality, and intended behaviors.

As a wireframe usually represents the initial product concept, styling, color, and graphics are kept to a minimum.

Wireframes can be drawn by hand or created digitally, depending on how much detail is required. Wireframing is a practice most commonly used by UX designers.

This process allows all stakeholders to agree on where the information will be placed before the developers build the interface out with code.

When does wireframing take place?

The wireframing process tends to take place during the exploratory phase of the product life cycle. During this phase, the designers are testing the scope of the product, collaborating on ideas, and identifying business requirements. A wireframe is usually the initial iteration of a webpage, used as a jumping-off point for the product’s design. Armed with the valuable insights gathered from the user feedback, designers can build on the next, more detailed iteration of the product’s design—such as the prototype or mockup.

What is the purpose of wireframing?

Wireframes serve three key purposes:

Wireframes keep the concept user-focused

Wireframes are effectively used as communication devices; they facilitate feedback from the users, instigate conversations with the stakeholders, and generate ideas between the designers. Conducting user testing during the early wireframing stage allows the designer to harbor honest feedback, and identify key pain points that help to establish and develop the product concept.

Wireframing is the perfect way for the designers to gauge how the user would interact with the interface. By using devices such as Lorem Ipsum, a pseudo-Latin text that acts as a placeholder for future content, designers can prompt users with questions like “what would you expect would be written here?”. These insights help the designer to understand what feels intuitive for the user, and create products that are comfortable and easy to use.

Wireframes clarify and define website features

When communicating your ideas to clients, they may not have the technical lexicon to keep up with terms like “hero image” or “call to action.” Wireframing specific features will clearly communicate to your clients how they’ll function and what purpose they’ll serve. Wireframing enables all stakeholders to gauge how much space will need to be allocated for each feature, connect the site’s information architecture to its visual design, and clarify the page’s functionality.

Seeing the features on a wireframe will also allow you to visualize how they all work together—and may even prompt you to decide to remove a few if you feel they’re not quite working with the rest of the page’s elements. The wireframing stage is when stakeholders can be brutal!

Wireframes are quick and cheap to create

The best part about wireframes? They’re incredibly cheap and easy to create. In fact, if you have a pen and paper to hand, you can quickly sketch out a wireframe without spending a penny. The abundance of tools available means you can also build a digital wireframe within minutes (we’ll talk more about that a little later on!).

Often, when a product seems too polished, the user is less likely to be honest about their first impressions. But by exposing the very core of the page layout, flaws and pain points can easily be identified and rectified without any significant expenditure of time or money. The later it gets in the product design process, the harder it is to make changes!

How to make your wireframe in six steps

- Do your research

- Prepare your research for reference

- Make sure you have your user flow mapped out

- Draft, don’t draw. Sketch, don’t illustrate

- Add some detail and get testing

- Start turning your wireframes into prototypes

How to make your wireframe good: Three key principles

Examples of wireframes

and to know more About GitHub Pages visit this link

and to know more About GitHub Pages visit this link

HTML basics !

So what is HTML?

HTML is a markup language that defines the structure of your content. HTML consists of a series of elements, which you use to enclose, or wrap, different parts of the content to make it appear a certain way, or act a certain way. The enclosing tags can make a word or image hyperlink to somewhere else, can italicize words, can make the font bigger or smaller, and so on. For example, take the following line of content:

My cat is very grumpy

If we wanted the line to stand by itself, we could specify that it is a paragraph by enclosing it in paragraph tags:

<p>My cat is very grumpy</p>

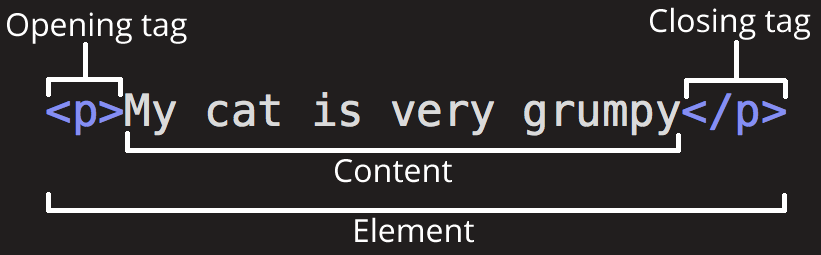

Anatomy of an HTML element

Let’s explore this paragraph element a bit further.

The main parts of our element are as follows:

-

The opening tag: This consists of the name of the element (in this case, p), wrapped in opening and closing angle brackets. This states where the element begins or starts to take effect — in this case where the paragraph begins.

-

The closing tag: This is the same as the opening tag, except that it includes a forward slash before the element name. This states where the element ends — in this case where the paragraph ends. Failing to add a closing tag is one of the standard beginner errors and can lead to strange results.

The content: This is the content of the element, which in this case, is just text.

The element: The opening tag, the closing tag, and the content together comprise the element.

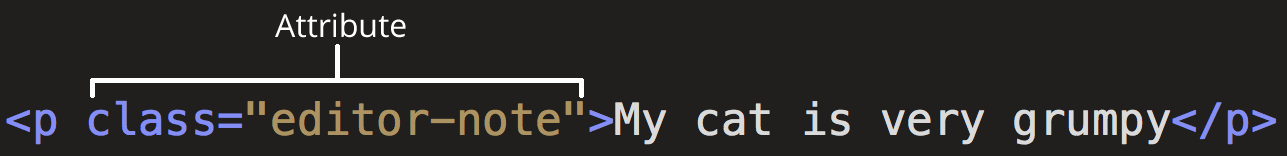

Elements can also have attributes that look like the following:

Attributes contain extra information about the element that you don’t want to appear in the actual content. Here, class is the attribute name and editor-note is the attribute value. The class attribute allows you to give the element a non-unique identifier that can be used to target it (and any other elements with the same class value) with style information and other things.

An attribute should always have the following:

-

A space between it and the element name (or the previous attribute, if the element already has one or more attributes).

-

The attribute name followed by an equal sign.

-

The attribute value wrapped by opening and closing quotation marks.

Note:

Simple attribute values that don't contain ASCII whitespace (or any of the characters " ' ` = < > ) can remain unquoted, but it is recommended that you quote all attribute values, as it makes the code more consistent and understandable.

Semantics

In programming, Semantics refers to the meaning of a piece of code — for example “what effect does running that line of JavaScript have?”, or “what purpose or role does that HTML element have” (rather than “what does it look like?”.)

Semantics in JavaScript

In JavaScript, consider a function that takes a string parameter, and returns an <li> element with that string as its textContent. Would you need to look at the code to understand what the function did if it was called build(‘Peach’), or createLiWithContent(‘Peach’)?

Semantics in CSS

In CSS, consider styling a list with li elements representing different types of fruits. Would you know what part of the DOM is being selected with div > ul > li, or .fruits__item?

Semantics in HTML

In HTML, for example, the <h1> element is a semantic element, which gives the text it wraps around the role (or meaning) of “a top level heading on your page.”

<h1>This is a top level heading</h1>

By default, most browser’s user agent stylesheet will style an <h1> with a large font size to make it look like a heading (although you could style it to look like anything you wanted).

On the other hand, you could make any element look like a top level heading. Consider the following:

<span style="font-size: 32px; margin: 21px 0;">Is this a top level heading?</span>

This will render it to look like a top level heading, but it has no semantic value, so it will not get any extra benefits as described above. It is therefore a good idea to use the right HTML element for the right job.

HTML should be coded to represent the data that will be populated and not based on its default presentation styling. Presentation (how it should look), is the sole responsibility of CSS.

Some of the benefits from writing semantic markup are as follows:

-

Search engines will consider its contents as important keywords to influence the page’s search rankings (see SEO)

-

Screen readers can use it as a signpost to help visually impaired users navigate a page

-

Finding blocks of meaningful code is significantly easier than searching through endless divs with or without semantic or namespaced classes

-

Suggests to the developer the type of data that will be populated

-

Semantic naming mirrors proper custom element/component naming

When approaching which markup to use, ask yourself, “What element(s) best describe/represent the data that I’m going to populate?” For example, is it a list of data?; ordered, unordered?; is it an article with sections and an aside of related information?; does it list out definitions?; is it a figure or image that needs a caption?; should it have a header and a footer in addition to the global site-wide header and footer?; etc.

Semantic elements

These are some of the roughly 100 semantic elements available: